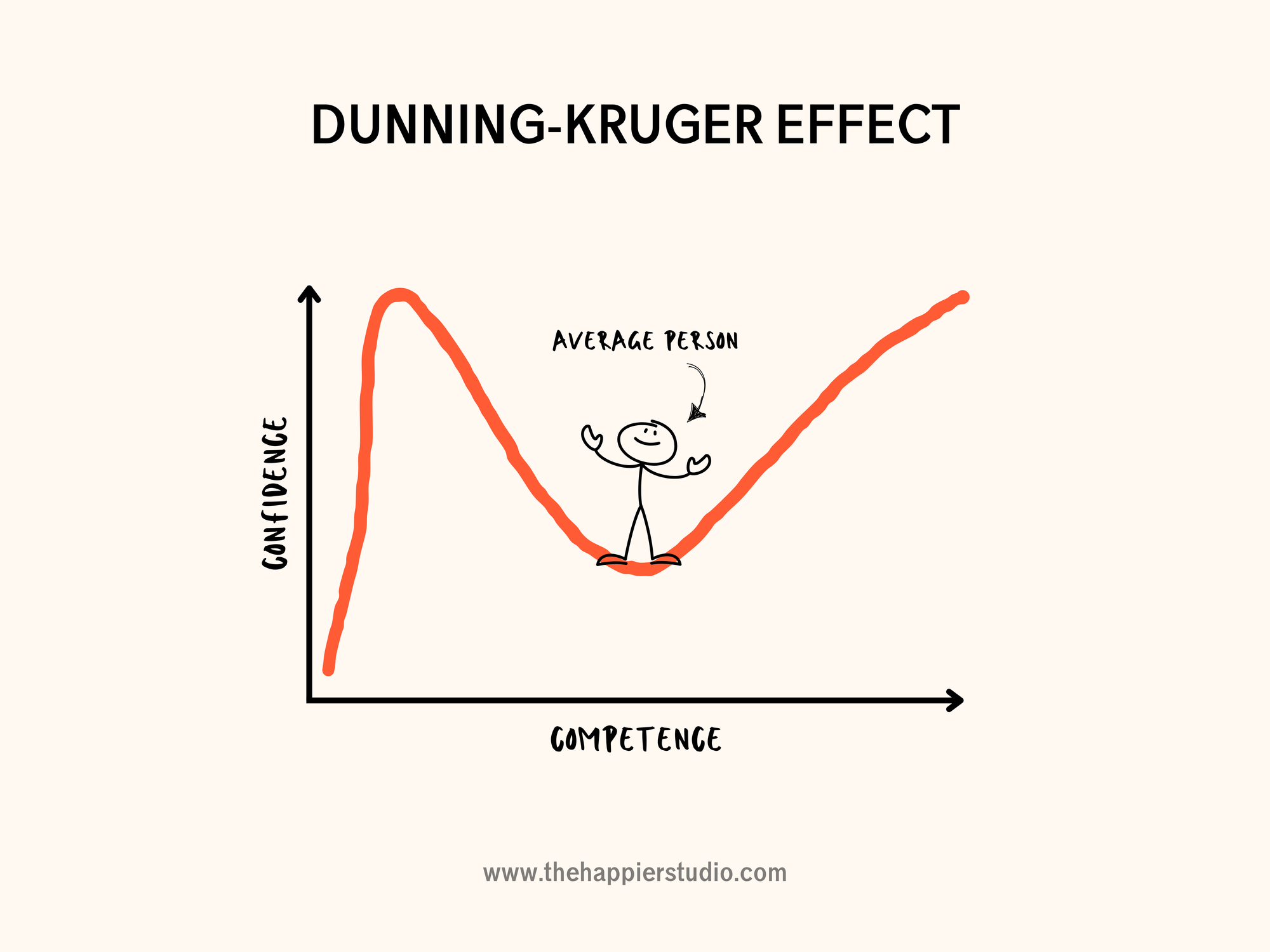

Have you ever noticed that people with the least knowledge on a topic often seem the most confident in their opinions? This is a classic example of the Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias where people with limited knowledge overestimate their competence, while those with higher expertise often underestimate theirs. This curious phenomenon reveals a gap between how skilled we think we are and how skilled we actually are.

What Is the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

The Dunning-Kruger effect was first identified in 1999 by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger. Through their research, they discovered that individuals who scored low on tests often rated their abilities as above average. Ironically, those who performed the worst felt the most confident. This effect occurs because people with low expertise lack the perspective to accurately assess their knowledge gaps—if you don’t know much about a subject, it’s hard to recognize how much you don’t know.

On the flip side, highly skilled people often underestimate their abilities, assuming that what’s easy for them must be easy for others. This underestimation can lead experts to downplay their knowledge or hesitate to share insights, believing their understanding is “normal.”

Why the Dunning-Kruger Effect Happens

This effect is primarily due to a lack of metacognition—the ability to evaluate our own knowledge accurately. When we’re just starting to learn something, our understanding is often surface-level. We might be able to recite a few facts, but we’re blind to the deeper complexities that only experts grasp. As a result, beginners are often overly confident about their understanding.

This overconfidence also stems from our desire to feel competent. It’s uncomfortable to feel lost or uncertain, so we may unconsciously choose to overestimate our abilities rather than face the reality of how much we still need to learn. Experts, meanwhile, tend to assume that if something is clear to them, it must be equally clear to everyone else—a phenomenon sometimes called the "curse of knowledge."

The Four Types of Knowledge

To better understand the Dunning-Kruger effect, it helps to break down knowledge into four types. Each type reveals why it’s easy to misjudge our expertise:

- Known Knowns: These are the things we’re aware that we know. For example, you know how to ride a bike or solve a basic math problem. This type of knowledge is familiar territory where we feel confident.

- Known Unknowns: These are the areas where we know we lack knowledge. For instance, you might know that you’re unfamiliar with advanced physics, so you’d approach it cautiously or seek expert help.

- Unknown Knowns: These are things we know but don’t realize we know. These often become apparent when someone points out that we’re applying a skill without conscious effort, like social cues or certain problem-solving techniques.

- Unknown Unknowns: This is the most challenging category and a key driver of the Dunning-Kruger effect. These are the things we don’t know and aren’t even aware that we don’t know. It’s the blind spot that makes us overconfident, as we can’t recognize the gaps in our understanding.

The Dunning-Kruger effect mainly stems from those “unknown unknowns.” When we’re unaware of our knowledge gaps, we mistakenly assume we know more than we do. Recognizing that this category exists is essential for gaining a more accurate view of our abilities and for approaching new topics with humility.

Everyday Examples of the Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger effect pops up more often than we might think, impacting how we approach opinions, work, and even hobbies. Here are some common situations where this bias tends to show itself:

- Opinions on Public Issues: You’ve likely encountered people with strong opinions on politics, health, or education who, when pressed, can’t explain the basic facts. The Dunning-Kruger effect often makes us overconfident about things we’ve only heard about second-hand or skimmed in an article.

- Skills at Work: New employees might come in full of confidence, assuming they know everything they need to succeed. Over time, however, they discover the skills and experience they still need to develop. In contrast, seasoned professionals may be aware of the many nuances and challenges, leading them to downplay their own expertise.

- Learning New Hobbies: When we take up a new hobby, like cooking or playing an instrument, the initial stages are often exciting because progress comes quickly. But as we delve deeper, we start seeing just how much there is to master. Some may even quit at this stage, discouraged by the sheer amount of knowledge still to learn.

The Risks of the Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger effect isn’t just a quirky mental shortcut—it has real-life implications that can affect both personal and professional aspects of our lives.

- Poor Decision-Making: When we overestimate our knowledge, we make decisions with false confidence, overlooking critical information. This can lead to costly mistakes, whether in personal choices or professional settings.

- Damaged Relationships: People who consistently believe they’re right, even when they lack expertise, can come across as arrogant or dismissive, creating tension in relationships. This is especially true if they regularly challenge others without taking the time to understand opposing perspectives.

- Missed Opportunities for Growth: Overconfidence keeps us from seeking feedback or learning from others. When we assume we already know enough, we stop pushing ourselves to improve.

Controversies and Criticisms

Though widely accepted, the Dunning-Kruger effect has faced some scrutiny. Some researchers suggest that statistical artifacts might account for part of the effect, challenging its robustness. However, the general consensus remains that people tend to misjudge their abilities, especially in areas where they lack experience. Whether the effect is universal or not, the tendency to overestimate knowledge is something most of us experience.

How to Recognise and Overcome the Dunning-Kruger Effect

Recognizing our own limitations is the first step to overcoming the Dunning-Kruger effect. Here’s how to approach it:

- Stay Humble and Open: The more we learn, the more we realise how much we still don’t know. Embrace this humility—it keeps us open to learning and growth.

- Seek Feedback from Others: One of the best ways to see our blind spots is to get honest feedback. Ask for input from those who are more experienced, and be willing to take their insights to heart.

- Adopt a Beginner’s Mindset: Even if you have some experience, approach topics as if you’re a beginner. This can help you remain curious, willing to ask questions, and open to learning without assuming you already have all the answers.

- Embrace Lifelong Learning: Recognise that no matter how skilled we become, there’s always more to learn. Cultivating a mindset of lifelong learning helps counter the Dunning-Kruger effect by reminding us that expertise is a journey, not a destination.

The Dunning-Kruger effect highlights a humbling truth about knowledge: often, the less we know, the more confident we feel. By staying curious, seeking feedback, and committing to learning, we can avoid the pitfalls of this bias and foster a mindset that’s both growth-oriented and open to new perspectives.